Lately I’ve been learning the programming language rust. To challenge myself, I decided to create an interpreter for a small C-like language called “Tiny-C”. I’m still quite new to rust, but I am happy with the end result. You can view the code on GitHub at: https://github.com/AmberThrall/TinyC

Defining the language Link to heading

Before creating an interpreter for a language, we need to define how our language works and create a parser. I based the language

on Marc Feeley’s “Tiny-C Compiler” I came across on GitHub. It supports if statements, if-else statements, while statements and do statements. While Feeley’s compiler only supports four binary operators (+, -, < and =), I decided to include 12 binary operators (+, -, *, /, <, >, <=, >=, ==, =, && and ||). I’ve also included a single function print built-in to the language which simply prints out the provided value to stdout.

All variables represent 64-bit signed integers. There is no boolean type, so I made conditions evaluate “true” if they are greater than 0 and the various comparison operators return either 0 or 1.

For parsing, I decided to make use of the library pest instead of creating my own parser from scratch. The grammar for the language is as follows:

program = { SOI ~ statement? ~ EOI }

statement = {

if_else_statement

| if_statement

| while_statement

| do_statement

| block_statement

| expr_statement

| print_statement

| semicolon

}

if_statement = { "if" ~ paren_expr ~ statement }

if_else_statement = { "if" ~ paren_expr ~ statement ~ "else" ~ statement }

while_statement = { "while" ~ paren_expr ~ statement }

do_statement = { "do" ~ statement ~ "while" ~ paren_expr ~ semicolon }

block_statement = { "{" ~ statement* ~ "}" }

expr_statement = { expr ~ semicolon }

print_statement = { "print" ~ paren_expr ~ semicolon }

semicolon = { ";" }

paren_expr = { "(" ~ expr ~ ")" }

expr = { term ~ (op ~ term)* }

term = { id | int | paren_expr }

op = { "+" | "-" | "*" | "/" | "<" | ">" | "<=" | ">=" | "==" | "=" | "&&" | "||" }

id = @{ (ASCII_ALPHA | "_") ~ (ASCII_DIGIT | ASCII_ALPHA | "_")* }

int = @{ "-"? ~ ASCII_DIGIT+ }

WHITESPACE = _{ " " | "\t" | "\r" | "\n" }

COMMENT = _{ "/*" ~ (!"*/" ~ ANY)* ~ "*/" }

As an example program possible in Tiny-C, consider the following program which computes the $N$-th fibonacci number then prints it:

/* fib.tinyc

* Calculate the Nth fibonacci number and print it out.

*/

{

N = 10; /* The fibonacci number to calculate. */

if (N == 0) {

print(0);

}

else {

a = 0;

b = 1;

n = 1;

while (n < N) {

tmp = b;

b = a + b;

a = tmp;

n = n + 1;

}

print(b);

}

}

Creating the abstract syntax tree Link to heading

Pest’s parser returns a tree composed of Pairs following the derivation. These pairs allow us to step into each rule within a derivation and view the corresponding strings for each subrule. While we could evaluate the code with just this tree alone, it’d be better to clean it up into a easier to use format. I decided to create an enum Node representing each possible rule and their corresponding children.

pub enum Node {

Program {

statement: Option<Box<Node>>

},

IfStatement {

paren_expr: Box<Node>,

statement: Box<Node>

},

Int(i64),

// More nodes...

}

To create a new tree, we simply take our set of pairs pest gives us into a recursive function converting each rule into the proper node.

fn build_ast(pair: Pair<Rule>) -> Node {

match pair.as_rule() {

Rule::program => {

for record in pair.into_inner() {

match record.as_rule() {

Rule::statement => return Node::Program { statement: Some(Box::new(build_ast(record))) },

_ => ()

}

}

Node::Program { statement: None }

},

Rule::if_statement => {

let mut pairs = pair.into_inner();

Node::IfStatement {

paren_expr: Box::new(build_ast(pairs.next().unwrap())),

statement: Box::new(build_ast(pairs.next().unwrap()))

}

},

Rule::int => Node::Int(pair.as_str().parse().unwrap()),

// More rules...

_ => panic!("Unknown rule: {:?}", pair.as_rule())

}

}

Handling expressions: precedence climbing Link to heading

If you look at the three primary grammar rules corresponding to expressions

expr = { term ~ (op ~ term)* }

term = { id | int | paren_expr }

op = { "+" | "-" | "*" | "/" | "<" | ">" | "<=" | ">=" | "==" | "=" | "&&" | "||" }

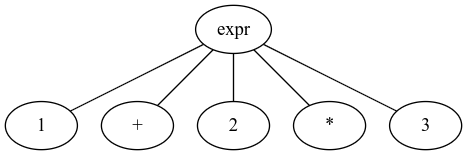

you may notice that expressions are composed of one long sequence alternating between terms and operators. Thus the tree for the expression 1 + 2 * 3 is:

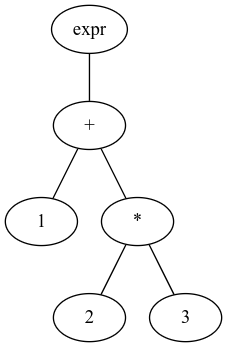

If we simply evaluate each child from left to right, our interpreter will claim that 1 + 2 * 3 = 9 instead of 7. We need to implement the order of operations creating a tree more like the following:

With this new tree, by evaluating from bottom to top we get the correct answer of 7. To create this tree, we make use of an algorithm called precedence climbing. You can read more about precedence climbing on Wikipedia. We first create an enum to represent operators:

pub enum Operator {

Plus,

Minus,

// More operators...

}

Then for each operator, we assign a precedence where the higher the precedence the farther down the tree the operator climbs.

impl Operator {

pub fn precedence(&self) -> u8 {

match self {

Operator::Plus => 3,

Operator::Minus => 3,

Operator::Times => 4,

Operator::Divide => 4,

Operator::LessThen => 2,

Operator::GreaterThen => 2,

Operator::LessThenOrEqual => 2,

Operator::GreaterThenOrEqual => 2,

Operator::Equals => 2,

Operator::NotEquals => 2,

Operator::And => 1,

Operator::Or => 1,

Operator::Assign => 0,

}

}

}

We’ll break up expressions into nodes called BinaryOp which has three parts: an operator, the left-hand side and the right-hand side.

pub enum Node {

// More nodes...

BinaryOp {

op: Operator,

lhs: Box<Node>,

rhs: Box<Node>

}

}

Now we can implement the actual algorithm.

fn build_expr_ast(mut pairs: Pairs<Rule>) -> Node {

let lhs = build_ast(pairs.next().unwrap());

let mut peekable = pairs.peekable();

build_expr_ast_climber(&mut peekable, lhs, 0)

}

fn build_expr_ast_climber(pairs: &mut core::iter::Peekable<Pairs<Rule>>, mut lhs: Node, min_precedence: u8) -> Node {

let mut peek = pairs.peek();

while peek != None {

let operator = Operator::from(peek.unwrap().as_str()).unwrap();

if operator.precedence() < min_precedence {

break;

}

pairs.next();

let lookahead = pairs.next();

let mut rhs = build_ast(lookahead.clone().unwrap());

peek = pairs.peek();

while peek != None {

let next_operator = Operator::from(peek.unwrap().as_str()).unwrap();

if next_operator.precedence() <= operator.precedence() {

break;

}

rhs = build_expr_ast_climber(pairs, rhs, operator.precedence() + 1);

peek = pairs.peek();

}

lhs = Node::BinaryOp {

op: operator,

lhs: Box::new(lhs),

rhs: Box::new(rhs)

};

}

lhs

}

The codes a bit messy, but it works! Now we just plug our new function build_expr_ast into build_ast.

fn build_ast(pair: Pair<Rule>) -> Node {

match pair.as_rule() {

// More rules...

Rule::paren_expr => build_ast(pair.into_inner().next().unwrap()),

Rule::expr => build_expr_ast(pair.into_inner()),

_ => panic!("Unknown rule: {:?}", pair.as_rule())

}

}

We now have a easily readable abstract syntax tree. In the final code, I have a function parse which parses the input string using pest, then calls build_ast returning the root node of the AST. I’ve also included the function Node::graphviz(&self, graphname: &str) to generate code of the tree to render with graphviz.

It is worth noting that precedence climbing can be built-in to the grammar itself, avoiding the work of having the parser perform this algorithm. But doing things that route makes adding more operators in the future harder. To see how easy it is to add new binary operators, check out the commit where I added && and ||.

Evaluating the tree Link to heading

With our easy to read abstract syntax tree built, we can now traverse down the tree evaluating nodes as we go along. I quickly created a Evaluator which stores our data and implements a basic stack.

pub struct Evaluator {

stack: Vec<HashMap<String, i64>>

}

impl Evaluator {

pub fn push_scope(&mut self) {

self.stack.push(HashMap::new());

}

pub fn pop_scope(&mut self) {

self.stack.pop();

}

pub fn write_stack(&mut self, ident: String, value: i64) {

if self.stack.len() == 0 {

self.push_scope();

}

// Search the stack backwards.

for scope in self.stack.iter_mut().rev() {

if let Some(x) = scope.get(&ident) {

scope.insert(ident, value);

return;

}

}

// Not already in the stack, add to top scope.

let scope = self.stack.last_mut().unwrap();

scope.insert(ident, value);

}

pub fn read_stack(&self, ident: String) -> Option<&i64> {

// Search the stack backwards.

for scope in self.stack.iter().rev() {

if let Some(x) = scope.get(&ident) {

return Some(x);

}

}

None

}

}

The stack works exactly as you’d expect. Whenever a block statement ({}) is encountered, a new scope is pushed. Within this new scope, we have access to variables initialized in lower scopes. At the end of the block statement, the scope is popped freeing all memory stored in that particular scope.

x = 1;

{ /* New scope pushed */

x = 3;

y = 2;

} /* Top scope popped, removing y. */

print(x); /* "3" */

print(y); /* Error: No variable named 'y' found in stack */

With the stack setup, we can now create our recursive function Evaluator::eval handling each possible node.

pub fn eval(&mut self, node: &Node) -> Result<Option<i64>, String> {

match node {

Node::Program { statement } => match statement {

Some(s) => self.eval(&s),

None => Ok(None)

},

Node::IfStatement { paren_expr, statement } => {

let condition = self.eval(&paren_expr)?.unwrap();

if condition > 0 {

self.eval(&statement)

} else {

Ok(None)

}

},

// More nodes...

Node::Id(x) => match self.read_stack(x.clone()) {

Some(v) => Ok(Some(v.clone())),

None => Err(format!("No variable named '{}' found in stack", x))

},

Node::BinaryOp { op, lhs, rhs } => {

let r = self.eval(&rhs)?.unwrap();

match op {

Operator::Assign => {

match &**lhs {

Node::Id(id) => {

self.write_stack(id.clone(), r);

Ok(Some(r))

},

_ => Err("Expected identifier to the left of '='".to_string())

}

},

Operator::Plus => Ok(Some(self.eval(&lhs)?.unwrap() + r)),

Operator::Minus => Ok(Some(self.eval(&lhs)?.unwrap() - r)),

// More operators...

_ => Err(format!("Unknown operator {:?}", op))

}

},

_ => Err(format!("Unsupported node '{:?}'", node))

}

}

With evaluating done, there isn’t much left to do. If we run

$ cargo run fib.tinyc

it will now parse the file, create the abstract syntax tree, then evaluate to print a single “55” to the terminal. I’m sure the code can be cleaned up, optimized and overall improved. But for a beginner rust project, I am happy with the outcome. If you want to see the code in full, it is available on GitHub at https://github.com/AmberThrall/TinyC.