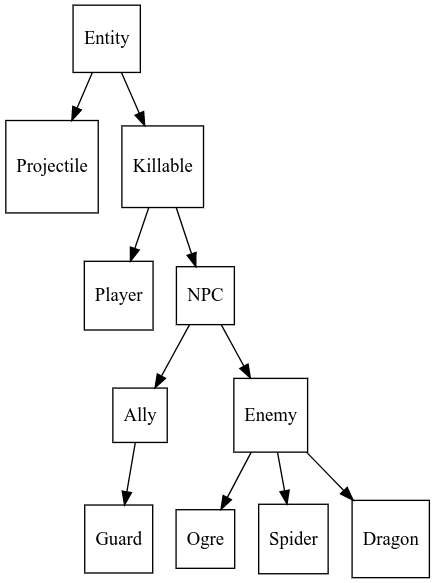

Imagine creating a game using an object oriented (OO) design. You may have a base class representing entities (“objects” placed throughout the world). Derived from entities you have several sub-classes representing various different behaviors.

As your game gets more and more complex, the more of a mess your class structure becomes. For example, consider the class structure drawn out above. If your team decided to create an important friendly NPC that was unkillable, major refactoring would be required. In otherwords, as time goes on, the harder adding new features to your game becomes.

Enter entity component systems (ECS). Instead of an OO architecture, we use a more data-driven approach. ECSs are composed of three parts:

- Entities: very simple, globally unique identifiers.

- Components: provide data structures to entities.

- Systems: provides behavior between components.

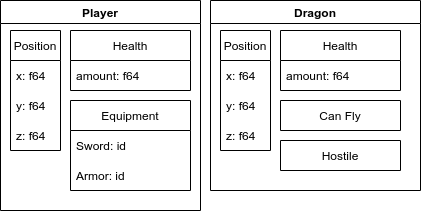

For example, consider the player and dragon entities described below:

Both have a Position and Health component, but have unique behavior that require special components. With this new design, adding new features to your game is as simple as creating the necessary components/systems and attaching them to the correct entities.

One may notice, that ECS has similarities to a relational database such as SQL. Entities represent keys, components represent tables, and systems represent queries.

If you want more information on ECS, I recommend Catherine West’s RustConf 2018 Keynote available on YouTube or their corresponding blog post.

First Attempt Link to heading

For a first crude attempt, we simple add a field for each possible component. Each component is stored in a HashMap allowing components to be attached specifically to certain entities. We also use a central “database” struct ECS to store and access each component.

pub struct Position {

x: f64, y: f64

}

pub struct Health(f64);

pub type Entity = usize;

pub struct ECS {

entities: Vec<Option<Entity>>,

position_components: HashMap<Entity, Position>,

health_components: HashMap<Entity, Health>,

}

In this example, I store a registry of entities with Vec<Option<Entity>>, where Entity is an alias for usize. When registering a new entity into the database, we simply look for the first None in the registry and replace it with the entity’s id. If the registry is full, we expand the vector.

impl ECS {

// More...

pub fn register_entity(&mut self) -> Entity {

match self.entities.iter().position(|entity| entity.is_none()) {

Some(id) => {

self.entities[id] = Some(id);

id

},

None => {

let id = self.entities.len();

self.entities.push(Some(id));

id

}

}

}

pub fn unregister_entity(&mut self, id: Entity) {

if id < self.entities.len() {

self.entities[id] = None;

self.position_components.remove(&id);

self.health_components.remove(&id);

}

}

pub fn attach_position_component(&mut self, id: Entity, position: Position) {

// impl...

}

pub fn attach_health_component(&mut self, id: Entity, health: Health) {

// impl...

}

}

This allows up to $2^{64}$ possible entities to be registered at once. If for some reason you need more than that, I recommend using the uuid crate. While this setup works just fine, things can get quite messy as you add more and more components to your game.

Generalized Attempt Link to heading

Instead of having a field for each possible component type, we want one field for all possible components. In rust we can achieve this with the

Any trait. More specifically, by combining the Any trait with TypeId, we can create a HashMap that can store one of each possible type.

pub struct AnyMap {

map: HashMap<TypeId, Box<dyn Any>>,

}

Some crates already exist for this (namely anymap), which should probably be used. To avoid dependencies, I’ve implemented a simple AnyMap myself.

impl AnyMap {

// More...

pub fn insert<T: 'static>(&mut self, value: T) {

self.map.insert(TypeId::of::<T>(), Box::new(value));

}

pub fn remove<T: 'static>(&mut self) {

self.map.remove(&TypeId::of::<T>());

}

pub fn get<T: 'static>(&self) -> Option<&T> {

self.map.get(&TypeId::of::<T>()).map(|x| x.downcast_ref::<T>().unwrap())

}

pub fn get_mut<T: 'static>(&mut self) -> Option<&mut T> {

self.map.get_mut(&TypeId::of::<T>()).map(|x| x.downcast_mut::<T>().unwrap())

}

}

This struct allows us to store any type, for example u32, with map.insert(0u32) and retrieve it with either map.get::<u32>() or map.get_mut::<u32>(). With AnyMap, we can replace the multiple component fields with a single field.

pub struct ECS {

entities: Vec<Option<Entity>>,

components: HashMap<Entity, AnyMap>,

}

Then attaching, detaching and borrowing entity’s components is as simple as looking up the entity, followed by calling the corresponding method from AnyMap.

impl ECS {

// More...

pub fn attach_component<T: 'static>(&mut self, entity: Entity, component: T) -> Result<(), String> {

match self.entities.iter().position(|x| *x == Some(entity)) {

Some(id) => {

self.components.get_mut(&id).unwrap().insert(component);

Ok(())

},

None => Err(format!("No entity with id {} found.", entity)),

}

}

pub fn detach_component<T: 'static>(&mut self, entity: Entity) -> Result<(), String> {

match self.entities.iter().position(|x| *x == Some(entity)) {

Some(id) => {

self.components.get_mut(&id).unwrap().remove::<T>();

Ok(())

},

None => Err(format!("No entity with id {} found.", entity)),

}

}

pub fn get_component<T: 'static>(&self, entity: Entity) -> Option<&T> {

if let Some(map) = self.components.get(&entity) {

map.get::<T>()

} else {

None

}

}

pub fn get_component_mut<T: 'static>(&mut self, entity: Entity) -> Option<&mut T> {

if let Some(map) = self.components.get_mut(&entity) {

map.get_mut::<T>()

} else {

None

}

}

}

With this, we now have a simple entity component system implemented in rust.

What About Systems? Link to heading

You may have noticed I didn’t talk much about systems. Implementing the various systems into your game is going to depend heavily on the task. In this example, I assume all systems are implemented as component methods. For example, for a render system you might create a sprite component with a render method that is called during the game loop.

Alternatively, you may decide to implement an event based system. For example, a physics system might only be ran whenever two entities collide.

I leave that up to you!

The full code can be seen on GitHub at: https://gist.github.com/AmberThrall/308e2d683dbd67bc91b681d4fa69d32c